The photo above shows a remnant of the reed beds that used to cover Nanhui and much of the Shanghai Peninsula. The photo is from Iron Track (31.003613, 121.907883), part of a reed bed 450,000 square meters in size lining the Dazhi River near Binhai. As the birding areas at Nanhui fall to the backhoe, future birders searching for species will turn to hidden corners such as this one.

This post is part of a series on the riches of the environment in Nanhui and the threats to those riches. Other posts in the series:

Reed Parrotbill, Symbol of Shanghai

Spoon-billed Sandpiper at Nanhui

Save the Nanhui Wetland Reserve!

by Craig Brelsford

Founder, shanghaibirding.com

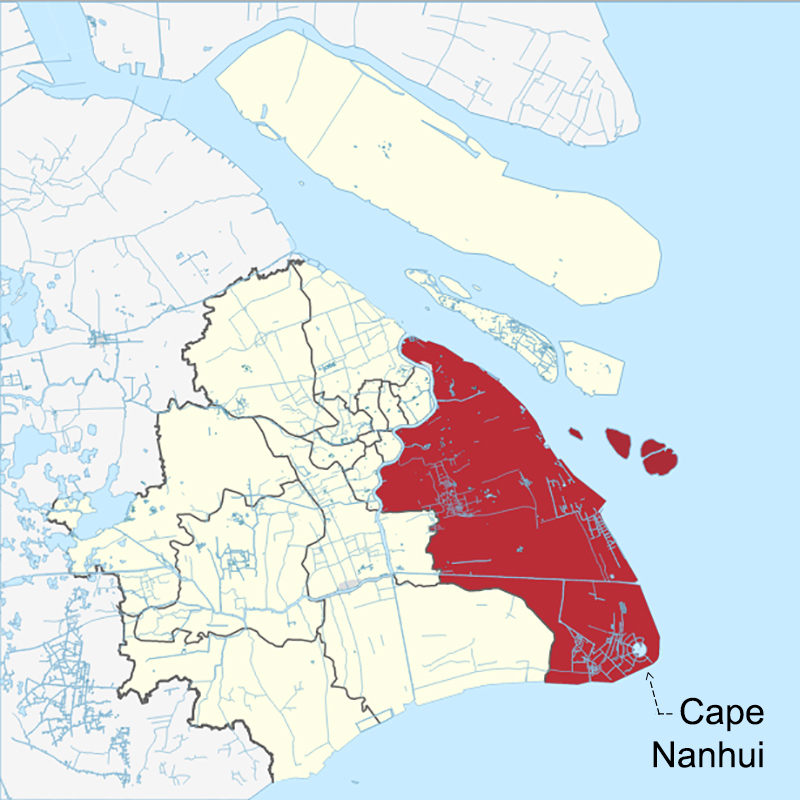

Though its position between the Yangtze River and Hangzhou Bay makes it among the richest birding areas on the coast of China, the southeastern tip of Pudong enjoys virtually no protection. The continued transformation of Cape Nanhui is likely, with the reed beds at particular risk. As the backhoes advance, birders ask: Where will we go to find our birds?

Answer: to the remnants.

Like archeologists examining a ruin, future birders at Cape Nanhui will scour the fragments of a once-great coastal wetland and try to imagine how the place once looked. Most of the land will have been transformed. Even now, in some of the agricultural areas around Binhai (31.007757, 121.885624) and Luchao (30.857299, 121.850590), nearly all of the original reed-bed habitat has disappeared.

If those future birders look hard, though, they will find intact pieces, islands of untouched habitat. Even around Binhai and Luchao, there are such places. Reed beds line man-made canals and larger waterways such as the Dazhi River, the mouth of which holds about 450,000 square meters of good reed-bed habitat. In these fragments, wild birds flourish, much as they always have done, though on a smaller scale.

Binhai lies to the north of the main birding areas east of Dishui Lake. Luchao is to the south. These towns border the 30-km stretch of coastline at Cape Nanhui. These built-up places point to the likely future of the areas just east of Dishui Lake, which have developed more slowly and to this day still hold pristine reed beds. (One of the largest covers 1.4 sq. km and has its center point at 30.876060, 121.945305.)

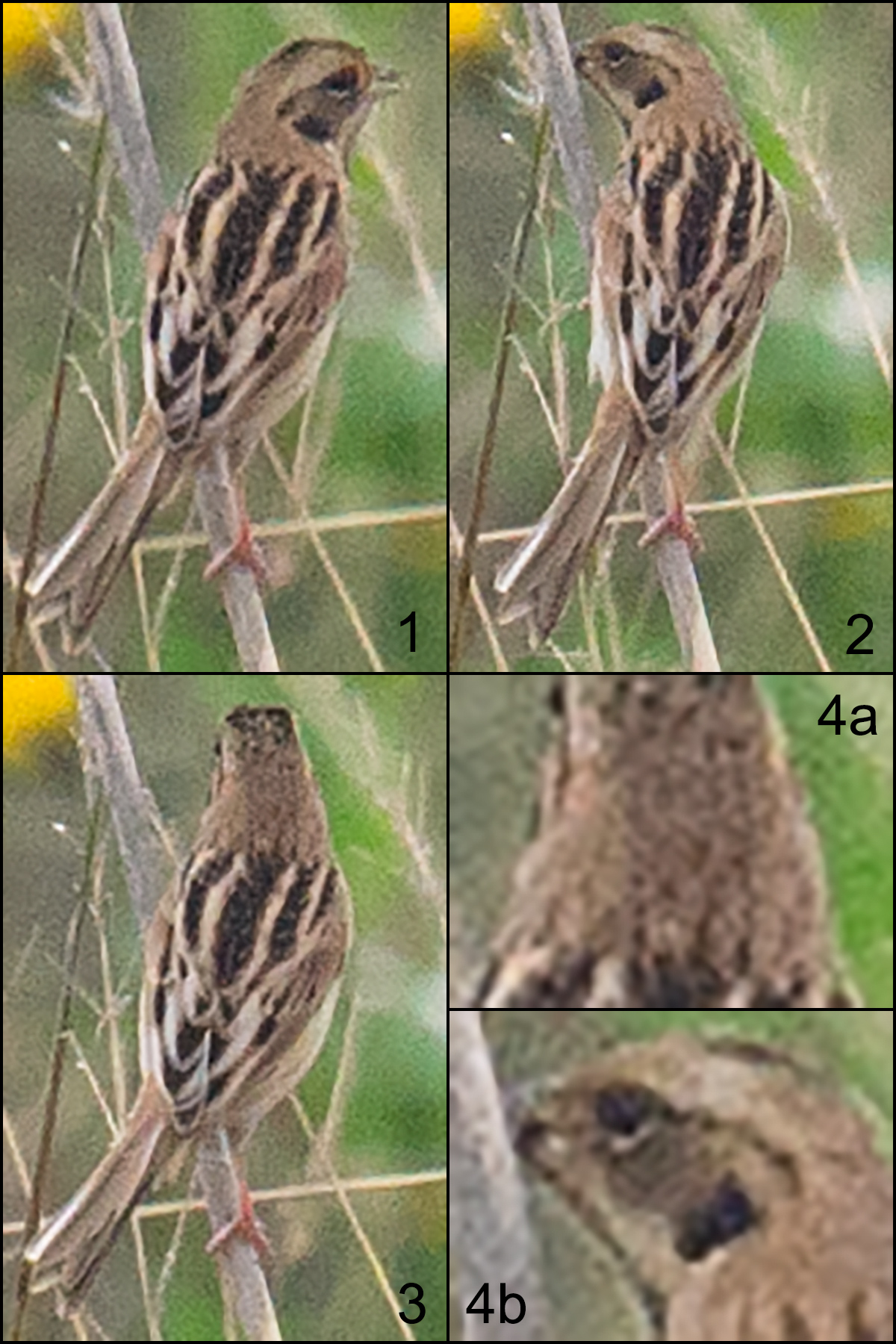

The reed beds east of Dishui are impenetrable—a wilderness within the city. We know that they are rich in birds, and we know that they hold species at risk, among them breeding Marsh Grassbird Locustella pryeri, listed as Near Threatened by IUCN. Judging by their frequency of occurrence at the edges of the reed beds, where they are regularly seen and heard, Near Threatened Reed Parrotbill must number in the high hundreds at Nanhui. Just this past Saturday, our team found Near Threatened Japanese Reed Bunting.

Even the tiny fragments near the towns hold a surprisingly high number of species. At a site (30.850707, 121.863662) north of Luchao, in reeds lining a canal at the base of the sea wall, Yellow-breasted Bunting have been present throughout November. On Saturday we found this Endangered species for the sixth time in six tries since our first sighting there on 5 Nov.

The site, part of a reedy area 75 m wide and 2500 m long, also yielded a small flock of Reed Parrotbill as well as wintering Chestnut-eared Bunting and Pallas’s Reed Bunting. Just north of the site, near Eiffel Tower (30.850531, 121.878047), there is an even smaller fragment of reed bed. There, we had juvenile Lesser Coucal.

Reed beds are an extremely rich habitat, and even a tiny area can hold many birds. Even if disaster continues to befall the large reed beds that still exist near Dishui Lake, not quite everything will have been lost. Birding will go on—in the remnants.

78 SPECIES AT CAPE NANHUI

On Sat. 19 Nov. 2016, Michael Grunwell, Elaine Du, and I birded Cape Nanhui. We found 78 species. We had Japanese Reed Bunting on the north side of the defunct wetland reserve (30.926452, 121.958517), the Hooded Crane that apparently spent a week in Nanhui, a single Baikal Teal (and presumably others shrouded in haze), a juvenile Lesser Coucal very much at home in remnant reed bed near Luchao, and Yellow-breasted Bunting at its reliable spot (30.850707, 121.863662).

Non-passerines: Tundra Swan (bewickii) 6 on the mudflats, Black-faced Spoonbill 6 in the defunct wetland reserve, Eurasian Spoonbill 45, Black-faced/Eurasian Spoonbill 30 in haze with bills tucked in, Black-tailed Godwit 1, Red Knot 2, Temminck’s Stint 1, Red-necked Stint 7, Dunlin 850.

Passerines: Brown-flanked Bush Warbler 1, Naumann’s Thrush 1, Chestnut-eared Bunting 15, Taiga/Red-breasted Flycatcher 1 (seen in poor light by Elaine; presumably the same confirmed Red-breasted Flycatcher found by Kai Pflug).

SIDE TRIP TO BINHAI FOREST PARK

On Saturday our team made its first trip since 31 Oct. 2015 to Binhai Forest Park (30.966324, 121.910289). The site yielded a late Mugimaki Flycatcher. More importantly, the brief visit gave us insights into the nature of migratory birds.

Though just 4.5 km inland, Binhai offers a mix of birds more akin to that of Century Park (22 km inland) than the coastal areas much nearer-by. Passerines moving through our region clearly hug the shoreline, especially around headlands such as Cape Nanhui.

Some of the smaller Nanhui microforests, such as Microforest 2 (30.926013, 121.970705), are about the size of a tennis court. But as they are a stone’s throw from the sea, they hold a much greater density of passage migrants than Binhai, which is 1600 times larger (1.5 sq. km) than Microforest 2.

HOW WE FOUND JAPANESE REED BUNTING

Michael, Elaine, and I were on the unpaved track on the north side of the defunct Nanhui reserve (30.926452, 121.958517). We were studying the roosting shorebirds and spoonbills. I got a call from Wāng Yàjīng (汪亚菁), who along with her husband Chén Qí (陈骐) found Swinhoe’s Rail at Nanhui last month. She told me a Hooded Crane was in the rice paddies 1.5 km north of us.

As we were rushing back to the car, I noted a lone reed bunting in the thick vegetation lining the dirt track. A lone reed bunting struck me as odd; Pallas’s Reed Bunting are common in the area and usually in flocks. I pulled out my camera and got a few images, which I did not have time to check. We got in the car and drove to see the crane.

Only the next day, when I sat down to look at Saturday’s photographic results, did I realize that I had photographed Japanese Reed Bunting Emberiza yessoensis.