Editor’s note: John MacKinnon is the co-author of A Field Guide to the Birds of China. Since its publication in 2000, this pioneering work has been the standard guide to the birds of China for foreign and Chinese birders alike. Herewith we present “Daxing’anling: Kingdom of the Great Owls.” It is about MacKinnon’s experiences with the owls of the Daxing’anling (大兴安岭) or Greater Khingan Range in northern Inner Mongolia. The photo above, taken by Li Jixiang, is of Ural Owl, one of the great owls of that remote and wild region. — Craig Brelsford

by John MacKinnon

for shanghaibirding.com

She is big. Wow, she is big. But she is beautiful and she knows it. She watches me with a disdain that most beautiful ladies seem to acquire. She is a hunter—a killer, but she has every right to be so. She is the Great Grey Owl, and I have been her admirer, hoping to meet her for many years.

She is perched only 2 metres off the ground in a flimsy larch bush that looks too weak to support her great size. But in fact she is lighter than she looks. Most of her bulk is feathers. The Great Grey Owl is marginally the longest owl in the world from head to tail, and the only two or three species that may be able to outweigh her are also here in the forests of Genhe Wetland Park of Daxing’anling: Eurasian Eagle-Owl, Blakiston’s Fish Owl and Snowy Owl.

Suddenly she hears a movement below her and pounces. A few moments scrabbling in the grass and she rises up again on silent, slow wing beats to settle on another small bush a few metres away. But now she has a large lemming in her beak. She transfers the lemming to the safer grasp of her foot then launches off on wide wings low over the ground, through a small clump of trees then out of sight into the larch forest beyond. I know she must have young to feed, and I want to see them also.

But before I find her young, I meet her two boyfriends a few hundred metres apart along the same trail leading deeper into the tall larch forest. Like Madame, they are relatively tame, and I can approach quite close to take photos. One has got wet in the night rain and looks rather miserable with straggly wet feathers. They are smaller than the female, but still pretty large. I am gradually getting to understand their habits. They are more diurnal than I expected, and they hunt in clearings rather than in the dense forests.

But her nest is in the forest, and I still try to find out where, so I return to her favourite hunting area and watch her a few more times to see exactly where she flies each time she catches another lemming or vole.

As chief technical advisor of the Daxing’anling wetlands conservation project funded by the Global Environment Facility and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme, I have other duties to attend to. I can only steal occasional moments and weekends for treks in the woods looking for birds! I have to wait two weeks before I get the chance to return and find where she hides her young.

Meanwhile, Deputy Director Li Ye of the nearby Hanma Nature Reserve has found another nest of Great Grey Owl and has taken great shots and video of the male bringing food for his mate, who sits on a large platform of sticks—probably an old crow’s nest—where she tends to two small chicks.

When I return to Genhe in July, I find Madame hunting in the same area as previously, but this time she flies less far into the forest between catches, and this time I can hear the weak, hoarse calls of a youngster. I find the young fledgling clumsily clambering about in the larch trees and making short flights from tree to tree. But I find only one baby—a fluffy fellow—already quite large but lacking the great broad face disk of the parents. It pours with rain, and I have to move on back to Hanma, where I have another owl family to monitor. By August I return to find there are indeed two chicks—and looking very much mature, with clear concentric facial disk rings.

At Hanma it is the Ural Owl that lures me out into the dark forest at night. Ural Owl is a true wood owl and unlike Great Grey it nests in tree holes. It is smaller than the Great Grey, but at 54 cm it is still an impressively large bird. It looks, sounds, and behaves like a giant Himalayan Owl, which is a common species across much of China.

On a visit the previous year I had found and photographed two fully flying young fledglings, so I headed to the same spot, hoping to find they had bred in the same area. I was rewarded by finding an adult Ural Owl perched on the stump of a dead tree. I got some pictures in the dark. I had to use a flash, so the owl’s eyes reflect back spookily.

I head back to the cabin I stay in, seeing several Grey Nightjar on my way. Sometimes the nightjars perch on the road, sometimes in trees, and sometimes they give their strange clonking calls as they fly around catching mosquitoes. Did I not mention the mosquitoes? Wow, how can I forget. There were hundreds of them, and they settled all over me whenever I stopped to take pictures. Their swollen bites still itch a week later. But I am happy to have seen these wonderful owls and cannot wait to find them again in the winter, when the snow lies on the ground.

It is in the snow time that the owls of Daxing’anling really show what they can do. The great Snowy Owl is perfectly coloured to creep up on unsuspecting white Mountain Hare. Snowy Owl is large, with a lazy yellow-iris stare. It is pure white and variously speckled with black spots, which break up its shape and make it almost invisible in the snowy landscape.

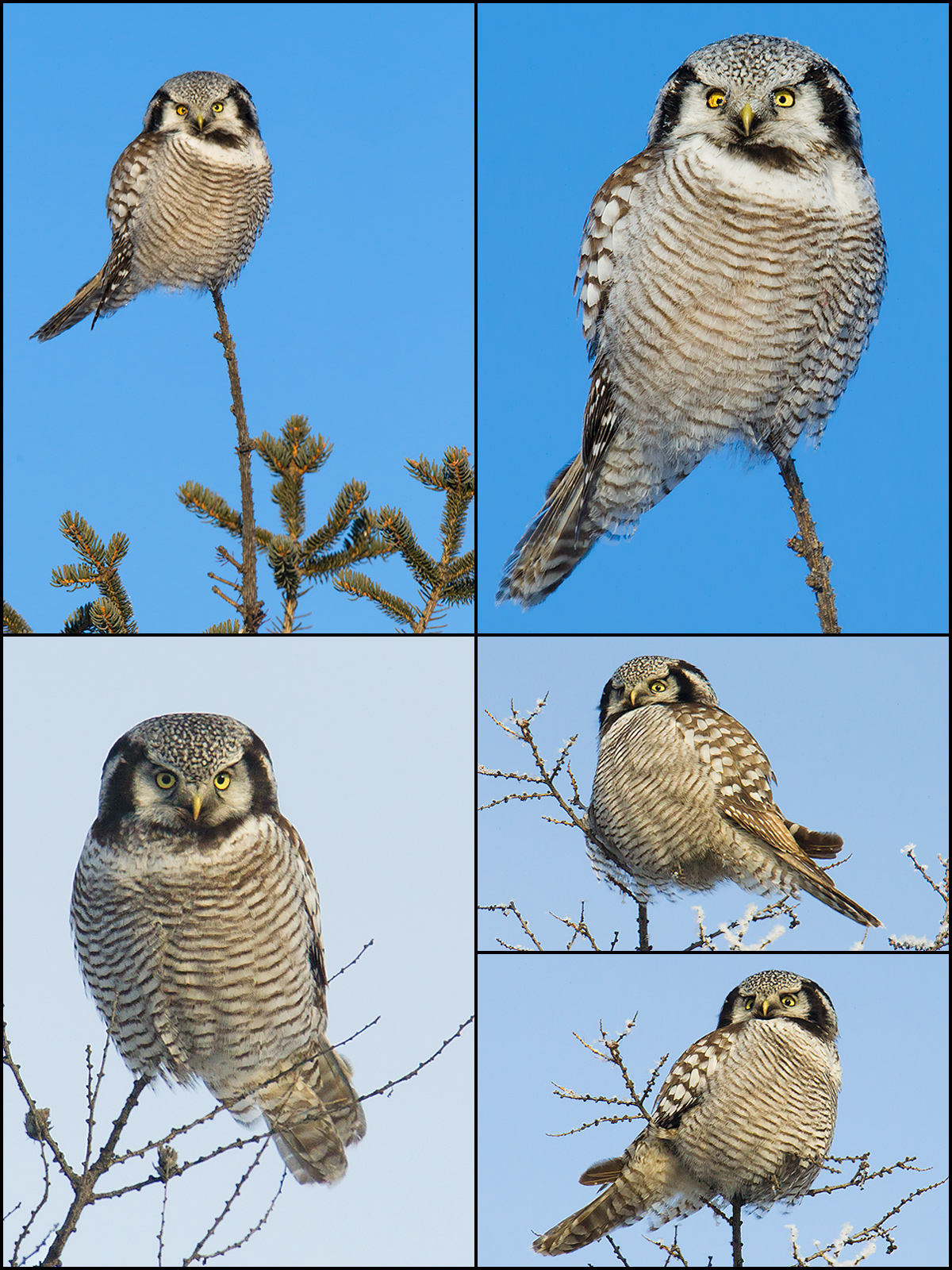

Another owl, Northern Hawk-Owl, is also largely white but with black ear muffs and thin stripes across its belly. The Northern Hawk-Owl catches birds and smaller prey in the woods. It is totally diurnal.

Other woodland owls such as the bulky Eurasian Eagle-Owl and its smaller cousin the Long-eared Owl are brown with black streaky plumage, long ear tufts, and fearsome orange eyes. In summer these two owls hunt chipmunks and pikas in dense forest, but in winter they move south or take up residence only in the most sheltered valleys. The smaller Boreal Owl lives in the tundra forests and is strictly nocturnal and rather solitary. Short-eared Owl is a grassland species that also moves to warmer locations in winter.

But the Great Grey stays put, hunting in the forest clearings from its low perches. This owl has amazing hearing and can detect voles and lemmings moving in their burrows underneath half a metre of snow. Like a polar bear catching seals beneath the Arctic ice, the owl can plunge to its own depth in snow and drag out these unsuspecting rodents.

In winter the larch trees lose their needle leaves. But the forest is not silent. Moose rummage in the frozen wetlands and find food beneath the snow. Lynx compete with Snowy Owl to catch Mountain Hare, which have also gone white for the winter.

Willow Grouse, stoat, and weasel also turn white for the winter. Bears are hibernating, but the huge spotted capercaillies are active in the larch trees, eating the buds and shoots for the next year’s leaves and already starting to fight for females with their load croaking calls, fanning their tails like turkeys and eyeing the world fiercely under their red eyelids.

Daxing’anling is all about winter. The winter lasts for nine months, and summer is short. And there she rules—ice queen of China’s most northerly forests—the Great Grey Owl.

LIST OF PLACE NAMES

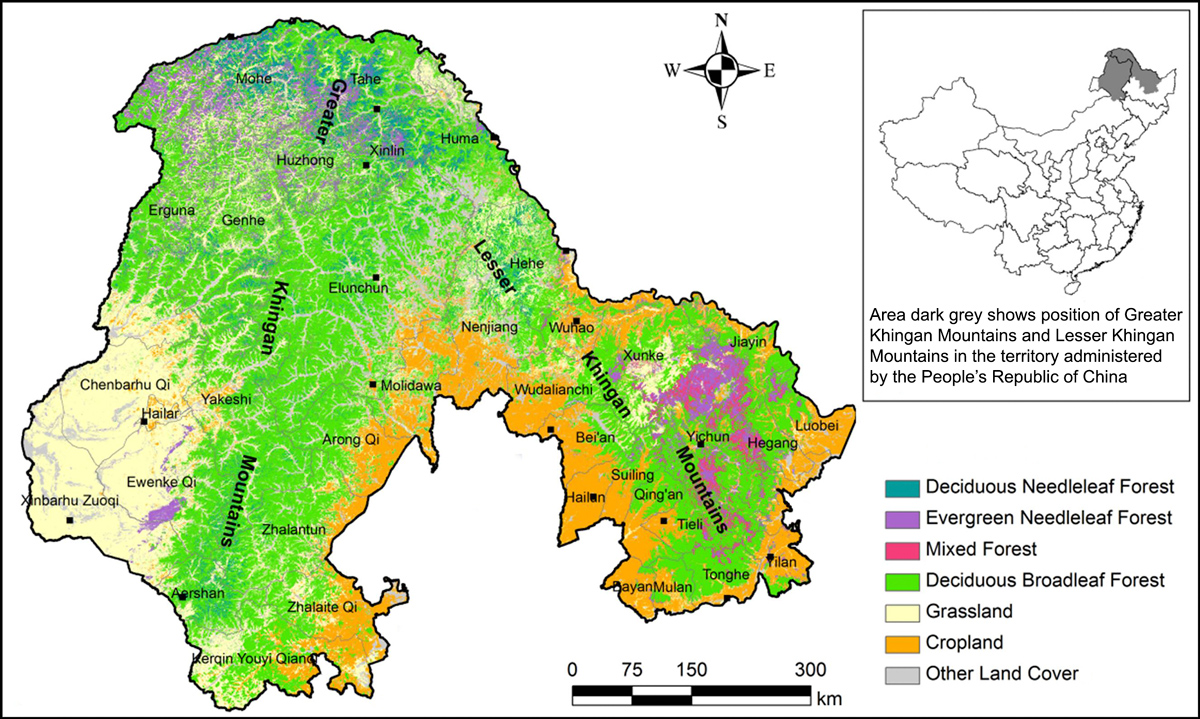

Daxing’anling (Dà Xīng’ānlǐng [大兴安岭])

Mountain range NE China (Inner Mongolia) dividing Greater Manchurian Plain & Mongolian Plateau. Range runs ca. 1200 km (744 mi.) S from Amur River, is broad in N & narrow in S, & is heavily forested throughout. Elevation of highest peak: 2035 m (6,675 ft.). In Inner Mongolia most of Daxing’anling lies within Hulunbeier Prefecture. Also called Greater Khingan Range, Greater Khingan Mountains.

Genhe Wetland Park (Gēnhé Yuán Guójiā Shīdì Gōngyuán [根河源国家湿地公园]): nature reserve Hulunbeier, Inner Mongolia. Coordinates: 51, 122.

Greater Khingan Range, Greater Khingan Mountains: see Daxing’anling.

Hanma Nature Reserve (Dà Xīng’ānlíng Hànmǎ Guójiājí Zìrán Bǎohùqū [大兴安岭汗马国家级自然保护区]): protected area Hulunbeier, Inner Mongolia. 51.32475, 122.37784.

Hulunbeier (Hūlúnbèi’ěr Shì [呼伦贝尔市]): sub-provincial administrative area NE Inner Mongolia. Area: 263,953 sq. km. (101,913 sq. mi.). Area (comparative): larger than United Kingdom; slightly smaller than Colorado. Pop.: 2.6 million. Much of Greater Khingan Range lies in Hulunbeier. Officially Hulunbeier “city” (市).

Inner Mongolia (Nèi Měnggǔ Zìzhìqū [内蒙古自治区])

Province N China. Area: 1.18 million sq. km (456,000 sq. mi.). Area (comparative): twice the size of Texas. Pop.: 24.7 million. Officially, an “autonomous region” (自治区).

MORE ON JOHN MACKINNON

John MacKinnon has played a major role in the development of shanghaibirding.com. MacKinnon has authored posts for the site, he has visited Shanghai and birded with the shanghaibirding.com team, and he has served as a consultant and inspiration from the very beginning.

Read the posts MacKinnon has authored for shanghaibirding.com:

MacKinnon in the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang: The visit of the pioneering naturalist included an encounter with wolves and records of Willow Ptarmigan and Rock Ptarmigan. “We emerged on top of the world,” MacKinnon writes, “with views way into the distance across the Mongolian border.”

Well-spotted in the Bamboo: MacKinnon introduces the bird community of Jinfoshan, the highest peak in the Dalou Mountains in the city-province of Chongqing. “Whilst colleagues … swarmed the site with an array of expensive cameras and optics,” MacKinnon writes, “I stayed deep in the forests, looking for laughingthrushes.”

The Artistry of Karen Phillipps: In this post, written exclusively for shanghaibirding.com, MacKinnon describes the qualities that made the late Karen Phillipps a great wildlife artist. “She had a unique, inimitable style,” MacKinnon writes. “Her pictures are clean, vibrant, and beautiful.”

See also

Exclusive Interview with John MacKinnon: On the occasion of the publication of his Guide to the Birds of China, the pioneering naturalist talks with shanghaibirding.com about his new book, his long career in Asia, and the many attractions that mega-diverse China offers to birders.

John MacKinnon in Shanghai: We gave the great naturalist the Cape Nanhui Grand Tour, noting 84 species, among them Oriental Plover. A fine storyteller and keen wit, MacKinnon had us roaring with tales drawn from his six decades as a researcher in Asia.

MacKinnon’s new Guide and classic Field Guide: The Guide to the Birds of China, published in 2022, and its predecessor, the Field Guide to the Birds of China, published in 2000, are the most influential books ever written about the birds of China. Birders from Xinjiang to Hainan have come to depend on MacKinnon’s monumental works.