by Louis-Jean Germain

for shanghaibirding.com

In the spring and summer of 2017, I spent two months in the Siberian Arctic on the Yamal Peninsula, 5300 km northwest of Shanghai. shanghaibirding.com has given me this opportunity to tell you about my experience birding that remote land.

The place I visited on the Yamal Peninsula lies well north of the Arctic Circle. My first stay was in May and June. I saw the snow melting and waves of birds hurrying to find the best breeding spots. My second stay lasted from the third week of July to the third week of August, during which time I watched parents caring for their young and the first sign of the migration back to the southern latitudes.

THE YAMAL PENINSULA

From September to May, the Yamal Peninsula is covered in thick snow and ice. Temperatures fall below -40°C. The natural habitat is tundra, the circumpolar treeless belt that lies between the Arctic ice and the tree line (taiga). Tundra is characterized by permafrost, low temperatures, and low precipitation. The growing season is short—two to three months.

From the beginning of May to late August, the sun is above the horizon 24 hours a day, its heat melting the ice and snow. The upper layers of the permafrost thaw quickly, producing seasonal lakes and rivers and an intense growth of vegetation and water insects. The warm sun also melts the sea ice, leading to an intense phytoplankton bloom.

The vegetation of the tundra is dominated by cotton-grass (genus Eriophorum), Water Sedge Carex aquatilis, lichens, and a great variety of dwarf shrubs (Vaccinium). The latter produces berries, an important food for birds. Plants and insects, the latter mostly aquatic at this latitude, have developed strategies to resist the extreme cold. They spring back to life as soon as the thaw begins.

Throughout June, July, and August, the tundra is an environment rich in food and, except for Arctic Fox Vulpes lagopus, absent of predators. To take advantage of this remarkable environment, birds migrate here in their thousands, flying thousands of kilometers. As each bird fits into its unique ecological niche, it prepares to reproduce—reproduction being the main purpose of its flight to this harsh land.

INITIAL DISCOVERIES: SHOREBIRDS

I arrived at the end of May, equipped with my Nikon Monarch binoculars (10 x 42) and Nikon ProStaff 5 telescope (30x-60x). I had no camera, as I only draw and paint birds. To my amazement, the snow had not yet melted, despite the air temperature’s hovering around freezing. In this white landscape, almost no birds could be seen. An exception was Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus, attracted by human activity.

My disappointment did not last long. Two days after my arrival, the first rain of the year fell on the tundra, creating small ponds. Almost immediately, as if by magic, birds appeared: Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula, White Wagtail Motacilla alba, and the magnificent Snow Bunting Plectrophenax nivalis. My excitement was intense. What could motivate those birds to come to that place, still so inhospitable, with almost all the land covered by snow and the temperature around freezing?

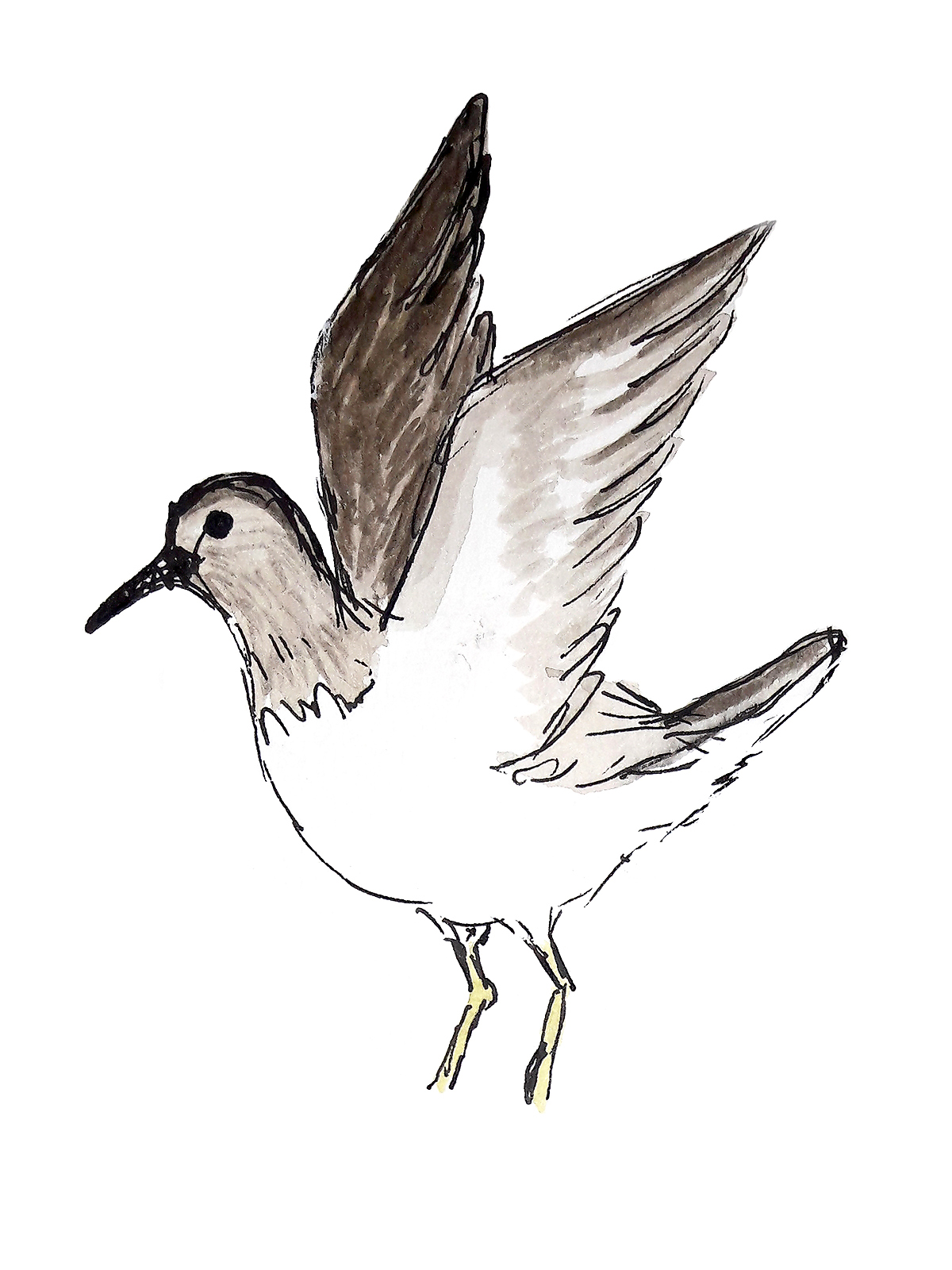

The next few days were even more exciting. As temperatures rose and lakes formed, I witnessed a massive arrival of birds. There were waterfowl (Steller’s Eider Polysticta stelleri, King Eider Somateria spectabilis) and passerines (Red-throated Pipit Anthus cervinus, Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus, Horned Lark Eremophila alpestris). The first calidrids to arrive were Little Stint Calidris minuta and Temminck’s Stint C. temminckii. The next day, I had Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula and Ruff Calidris pugnax, and the day after Curlew Sandpiper C. ferruginea, Dunlin C. alpina, Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres, Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola, and Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus.

After 10 days, I also observed a single Pin-tailed Snipe Gallinago stenura, Grey Phalarope Phalaropus fulicarius, and Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola.

These birds had started their trips two months earlier from places as distant as Africa and Australia. Some may have even passed through Shanghai. What a journey!

MATING DISPLAYS

By the beginning of June, the birds were restless. Male calidrids, which arrive before the females to compete for the best breeding territories, were displaying aggressively. As the females arrived, the males switched to a mating display.

Male Temminck’s Stint were hovering and calling noisily to the females. When a female was spotted, the male would chase her, running with his wings upward until she stopped. The male hovered delicately before mounting the female. The cloacal kiss lasted but an instant.

Common Ringed Plover were comical, fluffing their feathers and constantly running around.

The most astonishing behavior was that of Ruff, the only calidrid showing sexual dimorphism. Males are split into three plumage types, using various strategies to obtain mating opportunities at the lek. It was a magnificent sight to see more than 20 Ruff males fluffing their collar feathers and competing for the females.

LOONS

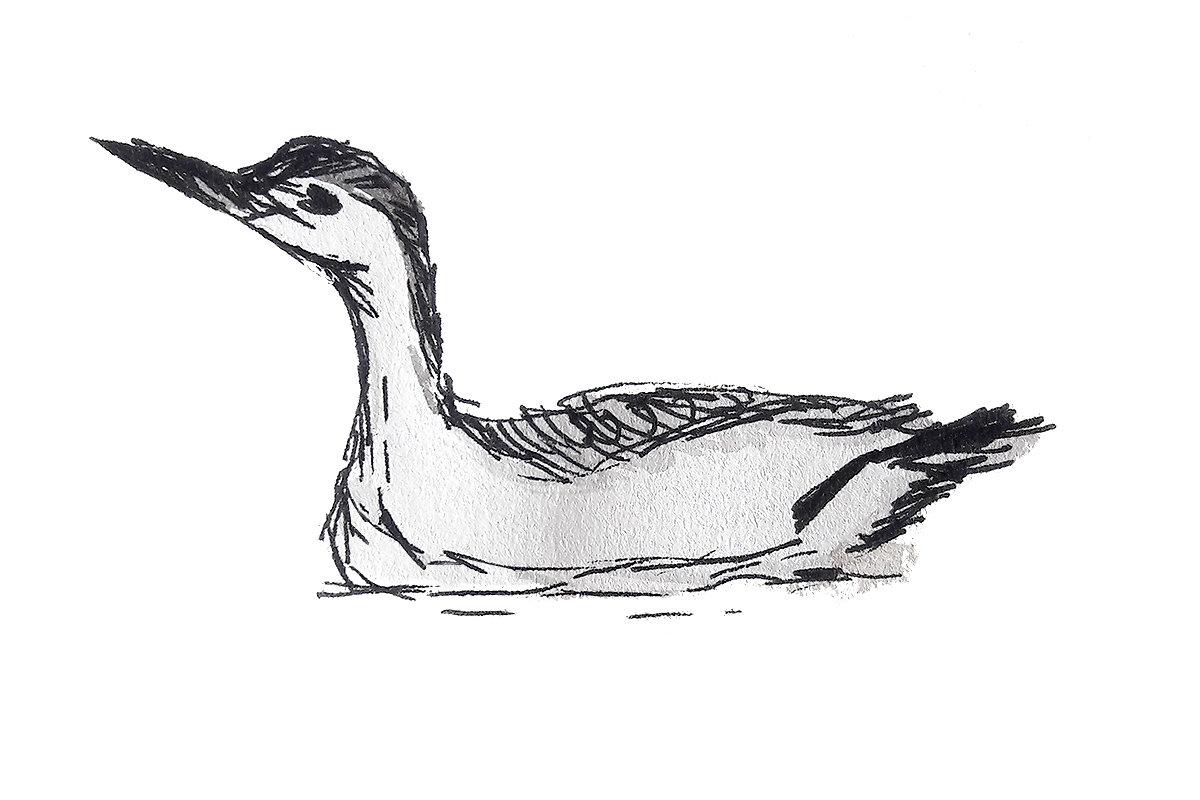

After 15 days, with the snow almost completely melted, I thought that the migration was over. Imagine my surprise when I noticed three huge birds on a large lake, low on the water, long necks straight up above the water and with bills curved upward. They were Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata. A pair and a single bird, probably a young male, had just arrived after the long trip up. The pair was looking for a place to nest, inspecting the bed of Water Sedge ringing the lake. The young tried to conceal the female but quickly yielded after an aggressive display by the other male.

The next day, while scanning the other side of the same lake, I saw another large bird swimming low on the water. The neck was stocky and the throat black with a deep purple sheen, brilliant in the sunlight. It was Black-throated Loon Gavia arctica. I was pleased to see this bird in breeding plumage after having seen it in winter plumage in Shanghai in March 2017.

BREEDING PLUMAGE

As a birder used to operating in temperate Shanghai, I was amazed by the extremely bright colors of the calidrids in June. Calidrids and plovers usually molt into their breeding plumage while migrating to the breeding grounds. It is always a great pleasure for Shanghai birders to observe shorebirds during the spring migration showing their pre-breeding plumage.

On the Yamal Peninsula in June, I beheld a pageant of the most fashionable plumages. I was rediscovering birds that I had previously observed in their duller winter plumage further south.

The English name of Phalaropus lobatus, “Red-necked Phalarope,” suits well the bird I was watching. Also, the Latin name of Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferruginea (ferruginous, rust-colored) described perfectly one of my favorite sandpipers.

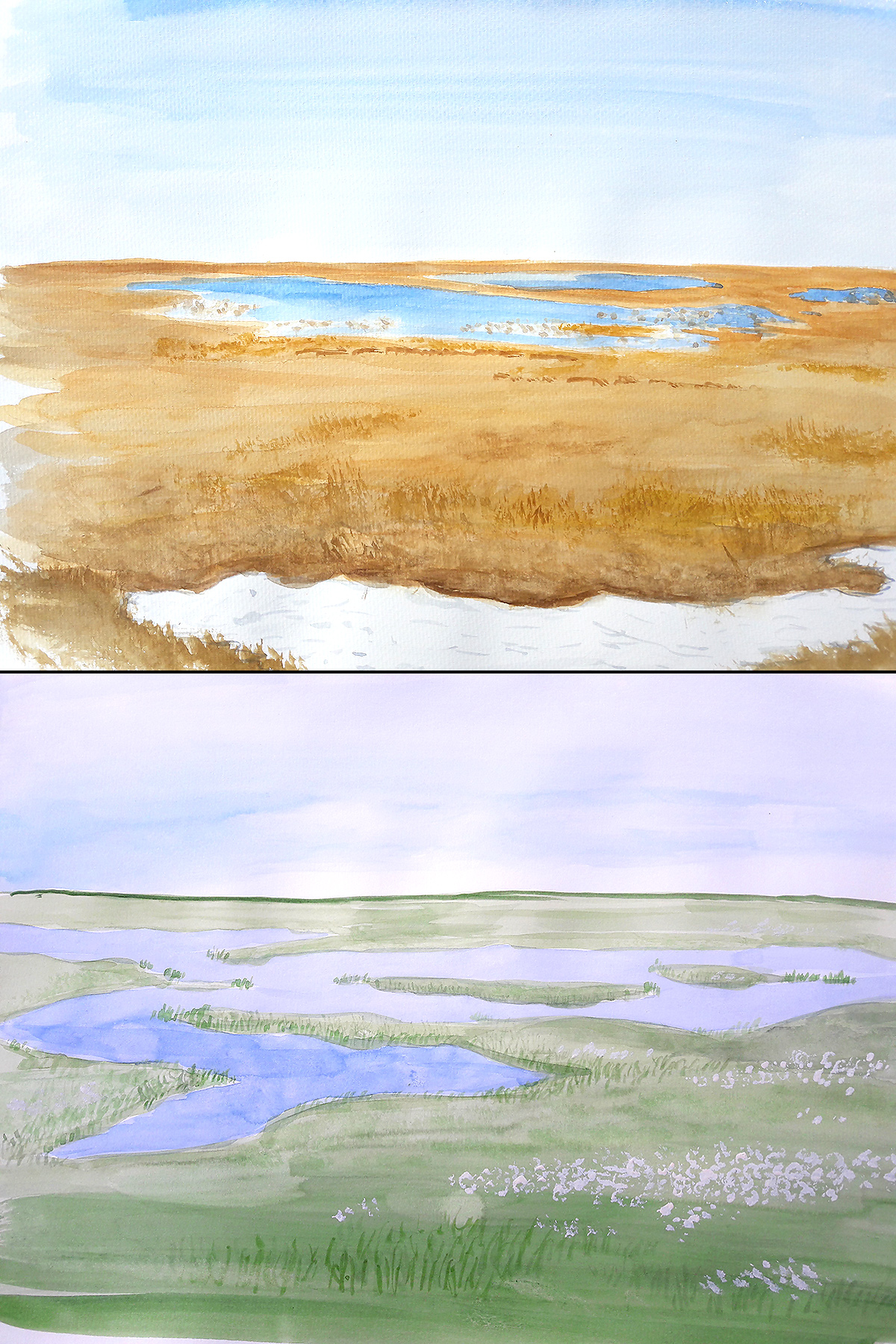

A LUXURIANT GREEN LANDSCAPE

During my second stay, from the third week of July to the third week of August, I discovered a different tundra. The yellowish-buff vegetation had been replaced by luxuriant green plants, cotton-grass, and flowers. I was amazed by this proof of the power of nature. How is it that this place, covered by snow and ice nine months of the year, during which time temperatures regularly fall to -30°C, could show such a remarkably green landscape during the summer? Gazing at the green tundra, I understood more deeply than ever why birds migrate.

Most of the chicks had hatched by that time, and most birds were inconspicuous, trying to hide their offspring from Arctic Fox and Lesser Black-backed Gull. Many drakes had left the area to molt. With patience and perseverance, I managed to spot the nests and offspring of several species.

I also noticed the parental behavior of some species. I was shocked by the devotion of the pair of Black-throated Loon, tirelessly diving for hours to feed their sole, frail offspring. Would this tiny bird be able to undertake a long migration in less than two weeks?

At the end of my stay, I noticed that the loons, both Red-throated and Black-throated, were gathering in groups of seven to nine individuals, showing obviously social displays such as powerful, simultaneous calls, diving, and water-splashing with their wings. The extraordinarily narrow window of time for breeding on the tundra was closing. The loons knew it.

TIME TO HEAD SOUTH

The birds with their offspring were about to perform another feat, the long migration south. The same wings that had carried them to this brief but rich northern feast would power them away as the killing cold set in.

My observation of the migratory birds on their breeding grounds was a learning experience that far exceeded my expectations. I hope that through my writing and paintings you have achieved a deeper appreciation of their amazing journey.

LIST OF BIRDS

During my stay on the Yamal Peninsula in the summer of 2017, I noted 40 species of bird, listed below. Hyperlinks connect to entries in shanghaibirding.com founder Craig Brelsford’s Photographic Field Guide to the Birds of China, published in its entirety on this website:

Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons

Long-tailed Duck Clangula hyemalis

King Eider Somateria spectabilis

Steller’s Eider Polysticta stelleri

Smew Mergellus albellus

Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula

Greater Scaup A. marila

Northern Pintail Anas acuta

Eurasian Teal A. crecca

Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus

Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata

Black-throated Loon G. arctica

Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola

Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula

Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres

Ruff Calidris pugnax

Curlew Sandpiper C. ferruginea

Temminck’s Stint C. temminckii

Dunlin C. alpina

Little Stint C. minuta

Pintail Snipe Gallinago stenura

Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola

Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus

Grey Phalarope P. fulicarius

Parasitic Jaeger (Arctic Skua) Stercorarius parasiticus

Pomarine Jaeger S. pomarinus

Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus

Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea

White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla

Horned Lark Eremophila alpestris

Northern Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe

Pechora Pipit Anthus gustavi

Red-throated Pipit A. cervinus

Meadow Pipit A. pratensis

White Wagtail Motacilla alba

Brambling Fringilla montifringilla

Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea

Arctic Redpoll A. hornemanni

Lapland Longspur Calcarius lapponicus

Snow Bunting Plectrophenax nivalis

THE BIRDS OF SIBERIA AND THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST

This post is part of shanghaibirding.com’s series on East Asian birds in Siberia and the Russian Far East:

• Sikhote-Alin: A Place Unparalleled for Experiencing the Birds of East Asia: The reserve in the Russian Far East, famous for being the home of Siberian Tiger, is also a world-class birding destination, holding Blakiston’s Fish Owl, Siberian Grouse, and Scaly-sided Merganser. Birders who dream of experiencing East Asian birds in their historical habitats should visit Sikhote-Alin.

• Birds of Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula (you are here)

• Kamchatka Leaf Warbler on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula: The first time I heard the song of Kamchatka Leaf Warbler, I knew it was a bird I had never heard before. Today we know that Kamchatka Leaf Warbler is distinct from Arctic Warbler. See my photos and hear my sound-recordings.

• Yellow-breasted Bunting on the Kamchatka Peninsula: Although its breeding range has contracted eastward some 5,000 km (3,100 mi.), Yellow-breasted Bunting is still doing well in Kamchatka, and there are indications that the species is recovering elsewhere. Hear my sound-recordings of its melodic song, recorded along the banks of the Zhupanova River in Kamchatka.

In addition to coverage of Siberia and the Russian Far East, shanghaibirding.com has extensive coverage of areas adjacent to the region:

Alaska

Northeast China

Xinjiang

Featured image: Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata, Yamal Peninsula, Russia. (Louis-Jean Germain)