by Jan-Erik Nilsén

for shanghaibirding.com

In my home country, Sweden, there are deep forests. They cover mountains and hills, encircle bogs and lakes, and fill gullies and valleys. There are spruces and pines in strange formations, with smaller stands of oak, birch, and aspen mixed in. It is a dark, mysterious forest, and it is vast. The Scandinavian forests are the western end of a belt, nearly unbroken, of forest that stretches across Eastern Europe, Siberia, and the Russian Far East into China.

With memories of the Scandinavian forests in mind, I wanted to find out what the forest would look like to the east some 8000 km (5,000 mi.). In 2015, in the excellent company of shanghaibirding.com founder Craig Brelsford and his wife and avid birder Elaine Du, I made a trip to Hulunbeier, the vast prefecture occupying northern Inner Mongolia. With an area of 264,000 sq. km (102,000 sq. mi.), Hulunbeier is slightly larger than the United Kingdom and slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Colorado.

On a map, Northeast China, or, as it is still sometimes known, Chinese Manchuria, resembles the head of a chicken facing east. Hulunbeier is the back of the head. At more than 53° north, the northernmost point of Hulunbeier is farther north than any point in the country of Mongolia and is nearly the northernmost point in China (that point being the front side of the chicken’s head nearby in Heilongjiang).

The forest up here is further north than the Mongolian steppes and connected to and similar to the Siberian taiga. At this latitude the winters are bitterly cold; the temperature can drop below -40°C/F. In the town of Mangui, signs along the road brag to the tourists about having the coldest winters in China. Summers are hot, with daytime temperatures often exceeding 25°C (77°F), and during our visit the forests were rather dry. The most common tree is larch, giving the forest a somber impression.

The mysterious and magic feeling of the Scandinavian forests was not at all present here. The link however to western Eurasia was apparent in birds such as Black Woodpecker, Hazel Grouse, Black Grouse, Great Grey Owl, and Northern Goshawk.

When you walk in the forest you will quickly attract a swarm of gnats. The abundant bugs irritate birders—and attract birds. The ample nourishment insects provide during the hot northern summer makes worthwhile the long flight from the Southeast Asian jungles. Among the passerines making the journey are Siberian Thrush, Red-flanked Bluetail, Mugimaki Flycatcher, Lanceolated Warbler, Gray’s Grasshopper Warbler, Arctic Warbler, Yellow-browed Warbler, Pallas’s Leaf Warbler, and Two-barred Warbler.

After a few days in the forest, we headed southwest along the Argun River, a tributary of the Amur River. Along the Argun River are grasslands, sometimes with fields of rapeseed flowers and other agricultural land, on moderately rolling hills, here and there with a stand of hardwoods. The boreal sun descends along a flatter trajectory in the evening, creating a soft and very pleasant evening light, reminiscent of Sweden. Along the Argun and its surrounding wetlands we found Baikal Teal, Steppe Eagle, Siberian Long-tailed Rosefinch, and Blyth’s Pipit. At dusk along every creek sang Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler.

We spent a few nights in Manzhouli, a railway port on the Russian border north of Hulun Lake. We saw the Russian Cyrillic script everywhere, and we had dinner in a Russian restaurant that served borscht, the famous Russian beetroot soup. The most extraordinary thing in Manzhouli were the swifts at our hotel. The shape of the roof tiles was perfect for swifts’ nests. The inner yard faced south, and under the roof tiles were nesting Common Swift. The swifts flew in and out, letting out their pleasant call in the closed backyard. The entrance of the very same hotel was facing north, and under the roof tiles in that direction, Pacific Swift were nesting. Apparently we had checked in at the very dividing line of the distributions of Common Swift and Pacific Swift!

Near Manzhouli we found smaller wetlands visited by waders in their hundreds. Red-necked Stint and Tringa members Common Greenshank, Spotted Redshank, and Wood Sandpiper had stopped here before continuing south.

We continued southwest to Hulun Lake. Here we found less agricultural land and more steppe, grazed by cattle, sheep, and horses. Here and there were Mongolian yurts holding restaurants serving roast lamb to Chinese tourists. On Chinese people’s list of must-see spots in China, the Mongolian steppes of Hulunbeier rank high. The prefecture, however, is so large that it never feels crowded, and the birding is good, particularly on the steppes. In the wetlands and overgrazed grasslands, we found Demoiselle Crane, Mongolian Lark, and flocks of Oriental Plover. Relict Gull patrolled the shores of Hulun Lake. The wetlands also had Pallas’s Reed Bunting, a flock of Little Curlew, and flocks of Swan Goose.

BIRDING THE TIBETAN PLATEAU

Let’s jump now far to the southwest, to a completely different region in China at an even higher elevation, and with different and very exciting habitats. The term Tibetan Plateau refers to a vast highland covering Tibet and extending into Qinghai and other jurisdictions. When we say “highland,” we are not talking about a few hundred meters in altitude. We mean superlatively high altitudes of 3500–5000 m (11,480–16,400 ft.). The landscape is nothing less than spectacular, and the power of nature is everywhere palpable. On the Plateau, one sees glaciers with creeks running down mountainsides, creeks crossing roads rather than roads crossing creeks, steep mountains, grasslands with yaks, alpine meadows full of yellow and violet flowers, and rich alpine scrub.

The weather can change in the blink of an eye. At one moment, one admires deep blue skies perforated by perfectly white summer cumulus. Take the next hairpin turn, and the road leads you right into a low hanging cloud and rain. The thunderstorms up here bring the most intense and severe lightning I have ever experienced. At this high elevation, the air is so thin that no thunder accompanies lightning.

Before my first trip to Qinghai in July 2014, I imagined that such high land would be fascinating. I could however hardly imagine that it would captivate me so much that I would return four more times to Qinghai. The first trip in 2014 was in the excellent company of shanghaibirding.com founder Craig Brelsford and British birder Brian Ivon Jones, both of whom, like me, had already been living for years in China.

Among the interesting birds up here are high-elevation specialists Red-fronted Rosefinch, Brandt’s Mountain Finch, Plain Mountain Finch, several species of snowfinch, and the stunning Güldenstädt’s Redstart. At wetlands we found the huge Black-necked Crane and on mountain ridges saw the silhouettes formed by families of Tibetan Snowcock. From utility poles along the road, Upland Buzzard and Saker Falcon scan the open landscape for prey. High above soars Himalayan Vulture.

Among birders it is less well known how good these highlands are for mammalian wildlife. Among the mammals we saw were Blue Sheep, Tibetan Wild Ass (Kiang), Tibetan Antelope, Tibetan Fox, and Tibetan Wolf. On another expedition to Qinghai in 2016, we had a breathtaking encounter with a Tibetan Lynx.

Two favorite Qinghai birds are the tit-warblers. What kind of birds are these strange and odd-colored species? Chickadees? Warblers? Tailorbirds? Based on their behavior I would incline to think they are related to Long-tailed Tit. White-browed Tit-warbler can be found in alpine scrub. Crested Tit-warbler is less common and can be found in conifer forests at elevations a bit lower.

“A bit lower”? Well, everything is relative, and in Qinghai one tends to label as “lower” elevation any place between 2500 m (8,200 ft.) and 3000 m (9,840 ft.). At these elevations are deserts and semi-deserts, with birds such as Henderson’s Ground Jay, Desert Wheatear, and Desert Whitethroat Curruca curruca minula. We came upon odd wetlands in the middle of nowhere, finding there Citrine Wagtail, Bearded Reedling, and breeding Tibetan Sand Plover.

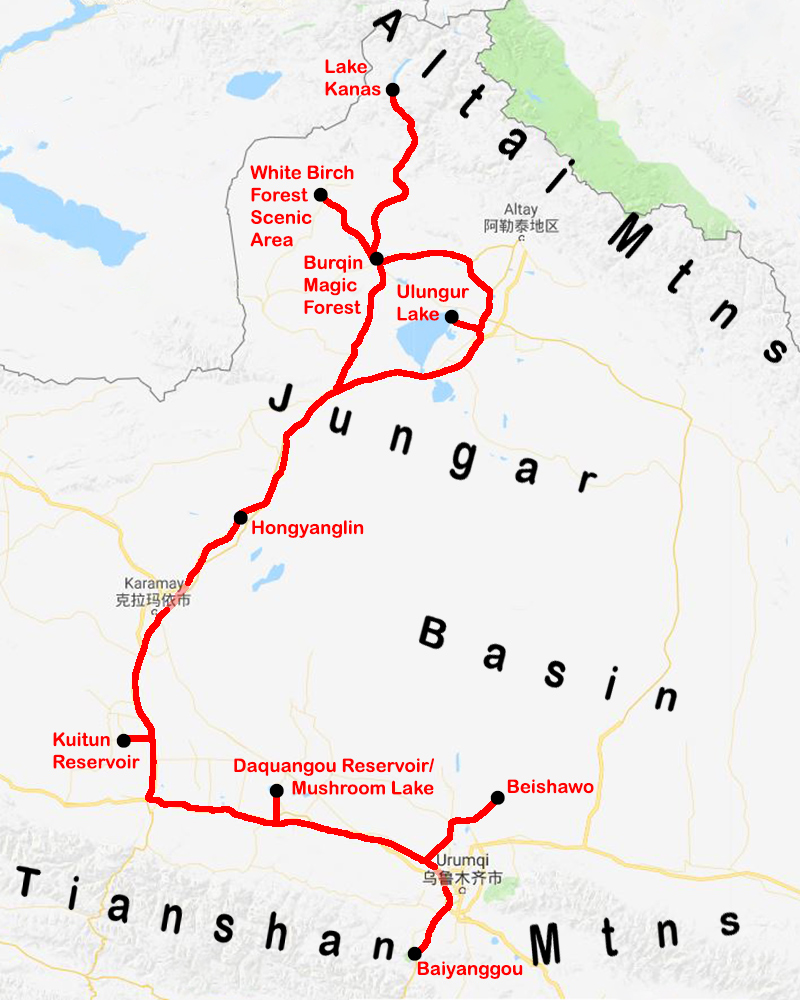

NOTES ON XINJIANG

Proceeding north from Qinghai, the Tibetan Plateau gives way to the Hexi Corridor in Gansu; westward, one enters another interesting birding area: Xinjiang. Habitat-rich and huge, Xinjiang is as big as Germany, France, and Spain combined. Located near the middle of the Eurasian supercontinent, Xinjiang is a four-hour flight from Beijing. Xinjiang has deserts and semi-deserts as well as lakes and wetlands reminiscent of Scandinavia. In the mountain ranges you’ll find conifer forests, and higher up grasslands and alpine meadows. The great variation of habitat provides a great variation of birds. Some—Common Chaffinch, European Goldfinch, Spotted Flycatcher, and Fieldfare—are familiar to European birders but occur nowhere else in China. Xinjiang also offers Central Asian specialties such as Pallas’s Gull, Caspian Gull, Long-legged Buzzard, Red-fronted Serin, Eversmann’s Redstart, and the beautiful Azure Tit.

Next: In the fourth and final post of my series, join me as I show you great coastal birding on the Bohai Sea and at Shanghai’s Cape Nanhui.

PHOTOS

THE THRILL OF BIRDING IN CHINA

This post is the third in Jan-Erik Nilsén’s four-post series on The Thrill of Birding in China. Click any link:

• The Thrill of Birding in China (Introduction): I stayed in China 12 years because I fell in love with the birding there, writes Swedish birder Jan-Erik Nilsén. China abounds in bird species because it is a large country on the Eurasian supercontinent with an endless array of habitats, from muddy seacoasts to high-altitude deserts. Forests in the north provide a link to Europe.

• The Thrill of Birding in Beijing: Expanding far beyond its urban core, the city-province of Beijing includes mountains, plains, lakes, and reservoirs. Miyun Reservoir delivers White-naped Crane and Jankowski’s Bunting, while the mountains hold East Asian classics Zappey’s Flycatcher and Grey-sided Thrush.

• The Thrill of Birding China’s Arid Interior (you are here)

• The Thrill of Birding Shanghai and the Bohai Sea Coast: Shanghai’s Cape Nanhui showed me an astonishing number of East Asian migrants, among them Japanese Yellow Bunting and Narcissus Flycatcher. Nearer my home in Beijing, the Bohai Sea coast gave me waders and gulls by the thousands, plus rarities Nordmann’s Greenshank and Spoon-billed Sandpiper.

THE BIRDS OF QINGHAI, XINJIANG, AND INNER MONGOLIA

Research the birds of Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia on shanghaibirding.com:

The shanghaibirding.com Index Page on Qinghai: Start here for a list of all our posts on birding in Qinghai. The Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong rivers rise in the sparsely populated province, which lies almost entirely on the Tibetan Plateau. Qinghai is big—three times larger than the United Kingdom and slightly larger than Texas. The average elevation is more than 3000 m (9,800 ft.).

The shanghaibirding.com Index Page on Xinjiang: Birding in Xinjiang is the adventure of a lifetime. In China’s largest and most northwesterly province, the birds, natural scenery, and people, including people wearing the uniforms of the state, are endlessly fascinating. See the complete list of our posts, including one by renowned author John MacKinnon.

The shanghaibirding.com Index Page on Inner Mongolia and Northeast China: Birding in Inner Mongolia and Northeast China is unlike birding anywhere else in China. The forests of the region, remnants of the ancient Manchurian forest that once stretched unbroken across the region, hold northern species absent further south in China. Start your research here.

Featured image: In Guoluo Prefecture, Qinghai, Jan-Erik Nilsén scans a pond, one of many “odd wetlands in the middle of nowhere” the Swedish birder studied in the vast province. The pond Nilsén is viewing, at 34.968553, 98.104906, lies a mile from the young Yellow River at an elevation of 4240 m (13,900 ft.). (Craig Brelsford)